Executive summary

Polish electoral law, like that of many countries in Europe, prohibits active electioneering on the eve and day of an election. This prohibition, which dates back to 1991, includes online statements by private individuals of support or attacks on specific politicians or parties.

A cursory glance at Twitter/X shows that this law is ignored by supporters of all parties.

Faced with this large-scale violation of Polish law, we used this as a test case of whether the platform would aim to abide by Member States’ rules. We found tens of thousands of violations viewed over 15 million times during the first round, which we were unable to report at scale due to technical issues with the platforms’ reporting systems. For the 20 flags that the platform did allow us to lodge, not a single one was deemed by X/Twitter’s moderation team to constitute active electioneering.

We notified X/Twitter of these surprising findings so that they would be able to fix them ahead of the second round, in the expectation that respecting the laws of the markets in which they operate would be their priority. These hopes were dashed as all shortcomings identified during the first round carried over to the second.

X/Twitter’s relationship vis-a-vis the laws of the countries it operates in remains unclear.

What is illegal under Poland’s electoral silence law ?

Under Article 107 of Poland’s Electoral Code, active electioneering is forbidden starting at midnight the day before an election: it is therefore illegal to publicly urge support for or against any candidate or party. These rules, which have been in place since the 1990s and are similar to those of other EU countries (such as France), aim to give voters a quiet period free of last-minute agitation.

While there has been debate in Poland and beyond as to whether such electoral silence laws remain fit-for-purpose in the social media era, the Polish public remains highly supportive of the mechanism and the Polish Electoral Commission (PKW) has consistently upheld the notion that what is illegal offline is also illegal online.

The electoral silence period therefore extends to digital media: social media posts, tweets, blog entries, etc. that promote a candidate are forbidden the day before an election, just as traditional ads or posters are.

Does Twitter/X abide by Polish law ?

Previous experience from France showed that, like other Very Large Online Platforms, X/Twitter has a lackluster record in complying with national electoral silence law.

To check if the platform had made any improvements over the last 12 months, we devised a simple two-stage process: navigate on the platform during the first round of the Polish presidential elections (May 18, 2025) to identify possible shortcomings, notify X/Twitter of these shortcomings and check during the second round (June 1, 2025) whether they had been fixed.

This protocol allowed us to not only check where possible shortcomings laid, but also whether X/Twitter was willing and able to fix those that they were notified of.

First round results: illegal content abounds, X/Twitter makes it hard to report, X/Twitter does not act when formally notified

A- Illegal content abounds

A query containing a few dozen election-related keywords (names of political candidates and parties as well as voting-related keywords such as wybory) on Meltwater, a social media listening tool, yielded over 65,095 unique tweets, posted during the electoral silence period and likely mentioning the elections.

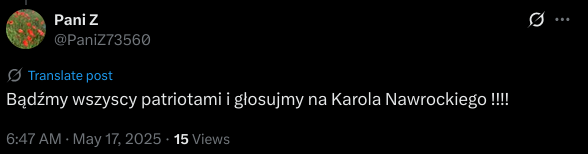

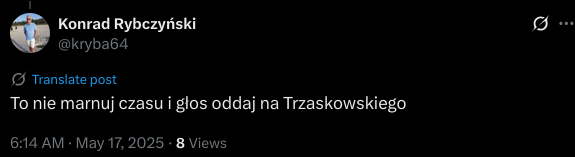

These tweets were then fed into an LLM tasked with identifying whether or not they constituted active electioneering (supporting or attacking a candidate or party). Out of the 65,095 tweets, 22,494 constituted active electioneering. This appears to be a transpartisan issue, as all corners of the political spectrum were represented. A human review of 100 randomly-selected posts validated the accuracy of the AI: in 99 cases, the human reviewer agreed with the LLM assessment.

These 22,494 likely-violative posts (accounting for over 15 million views) were just the tip of the iceberg as:

- the time period covered only a part of the electoral silence period,

- not all relevant posts were caught by the query (for instance, retweets were discarded and coded language used to refer to specific candidates was not picked up),

- only the text of the tweet itself was fed to the LLM (not the image nor the broader discussion thread).

While the total tally of violative posts during the first round cannot be reliably estimated, it is above the threshold to justify suspicions that systematic violations of the electoral silence period occurred.

It is unclear why a well-resourced social media platform wasn’t able to detect this content, given that a small non-profit such as Vigilia was. The entire file containing the URL of all suspected violations was shared with X/Twitter so that the platform would know what to look for in the second round.

B- X/Twitter makes it hard to report illegal content

X/Twitter makes it impossible to report infringing content at anything near the scale at which it appears. This effectively puts the notifiers at a systemic disadvantage compared to those breaking the law.

Specifically, while X/Twitter does have a “report illegal content in the EU” form, it is hardly usable to report anything like the tens of thousands of likely-violative tweets identified above as:

- After five reports in the span of a few minutes, the system puts the user in an effective ‘penalty box’ that makes it impossible to access the reporting form for a given period of time (in our experience, at least ten minutes). This soft reporting ban appeared to disappear when the email used to flag content was not associated with any X/Twitter account, for no evident reason.

- Effectively, only one piece of content can be reported at a time,

- The CAPTCHA used by X/Twitter is intricate and time-consuming to solve.

C- X/Twitter does not act

20 manifestly-illegal posts were flagged to Twitter using the on-platform “Report EU illegal content” form, under the “Illegal or harmful speech” category, with a sentence describing that the content went against Poland’s electoral silence period legislation.

Within hours, they had been reviewed by X/Twitter’s moderation system and, in 19 cases, were deemed “not subject to removal under the legal grounds of DSA Law in the EU” (the one exception being removed for “Defamation / Insult”).

In terms of process, this answer appeared puzzling as a- the flag was made under the Polish electoral silence law, not “DSA Law” and b- “DSA Law” purposefully does not state which content is or isn’t illegal (that is up to Member States in the overwhelming majority of cases), so mentioning it here in X/Twitter’s official answer suggests that the platform did not carry out basic due diligence.

On substance, the fact that not a single one of the tweets was deemed violative of the electoral silence law by X/Twitter appears to be in direct contradiction with the text and spirit of the law, official PKW guidance and well-documented examples of content considered violative.

Second round results: illegal content abounds, X/Twitter makes it hard to report, X/Twitter does not act when formally notified

Twitter was immediately notified of these shortcomings, during the electoral period's first round.

During the second round, we observed to what extent the issues had been fixed. Long story short, they hadn’t: the same query resulted in similar numbers of likely-violative content, as did the LLM filter. The reporting form remained unusable at scale for the same reasons listed above. The moderation decisions on content flagged were also the same (nine out of ten pieces of content reported were deemed non-violative “under DSA Law”, one was removed for “Defamation / Insult”).

As has become customary in such circumstances, communications with X/Twitter representatives resulted in their sidestepping most of the issues raised (points 1 and 2 above), with their answer focusing on just one point: looking into some of the specific flags to explain their rationale for not acting.

X/Twitter’s conclusion was that the reports were filed under the wrong category (“illegal or harmful speech” as opposed to “negative effects on civic discourse and elections”) so their teams were unable to act on them.

Beyond the obvious (“illegal speech” is a closer match than the vague “negative effects on civic discourse and elections” to report content that is illegal), this line of reasoning makes little sense as the one piece of content removed by X/Twitter was removed for a category other than the one it was reported under, proving that the platform’s moderation system does allow it to look at other categorical violations, if it wishes to.

In any case, X/Twitter offered no explanation as to why such content was proliferating on the platform nor was it able to fix the issue with the reporting form, making it impossible to flag content at anything near the scale of the problem.

.png)

.png)

.png)