The contemporary debate in many European countries has unfortunately polarized to the extent that calling out antisemitism can be disingenuously painted as support for the well-documented atrocities committed by the Israeli military in Gaza. Likewise, calling out dehumanizing speech against Palestinians, Arabs or Muslims in general can result in equally disingenuous allegations of minimizing the Oct. 7 tragedy or supporting antisemitism. Needless to say, neither is true here: two wrongs don’t make a right.

Nonetheless, to avoid accusations of partisanship that would needlessly distract from our goal (ensuring that Big Tech platforms actually comply with European laws, to the benefit of all Europeans), we kept a rough balance between reporting content targeting Jews and content targeting Palestinians/Arabs/Muslims.

The quick run-down

We report antisemitic, anti-Palestinian, anti-Arab and anti-Muslim content to social media platforms (Tiktok, Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn) when we believe it goes against one of the moderation policies that those companies pretend to have put in place (against harassment, hateful speech, glorification of violent groups such as nazis, etc…).

Most of the time, the platform says that the content actually isn’t violative. We disagree.

To judge who’s right, we go ask a neutral, certified, independent out-of-court dispute settlement body. In most cases, the independent referee says that we are and the platform is wrong.

Note: this table combines all notices filed for antisemitic, anti-Palestinian, anti-Arab or anti-Muslim content. It is current as of Nov 13 2025 and will be periodically updated.

Whether by design or incompetence, these platforms largely ignore their own rules when it comes to hateful speech. We strongly advise them to:

- redesign their systems to not create environments where hate proliferates,

- improve their moderation practices.

If history serves as a guide, we do not expect platforms to fix these issues of their own volition and consequently call on the European Commission and national regulators to force them to do so.

In more details

Platforms’ moderation systems make plenty of mistakes and someone else pays the price

Big Tech platforms routinely flout their own content moderation rules (not to mention European countries’ legislation), by taking down content that is perfectly valid (1, 2, 3, 4) or by leaving up content that goes against the policies they (pretend to) enforce (1, 2, 3).

Every day, social media platforms have to make billions of moderation decisions about content in hundreds of languages, to be checked against dozens of often-ambiguous policies (when does content cross the line from criticism to harassment? Where does Renaissance sculpture end and nudity begin?). Even if platforms invested much more than they do in content moderation (in our view, less than a minute or even just 10 seconds for a human moderator to rate a video isn’t enough), they would still get a lot wrong.

Platforms have created an impossible problem for themselves: grow, grow, grow at any cost to rake in advertising euros, even if that means they can’t keep up with moderation.

This is, in our view, a typical case of “private gains, public losses”. A recent example perfectly illustrates this: Meta’s internal documents show the company knowingly making USD 7 billion in 2024 from scam advertisements (think ‘get rich quick’ schemes or forbidden - and potentially dangerous - pseudo-medical products). The company has tools that can identify likely scams, but has made the decision that handling the issue wasn’t worth it, as possible fines would amount to less than USD 7 billion. So why moderate?

Meta wins, scammers win. Who loses? Those who fall for the scams, the banks or card issuers that might have to reimburse the fraudulent transactions, taxpayers who have to fund prevention and remediation efforts (reminder that Big Tech is still not paying its fair share of taxes in the EU, despite some countries’ digital services taxes).

This logic doesn’t apply only to Meta and not just to scams. Whenever platforms fail to properly moderate according to the rules they said they would set for themselves, someone else pays the price.

That price can be limited (seeing a mean tweet), moderate (call for the extermination of one’s religious group), severe (targeted death threats), debilitating (an influencer making their living off their audience losing their account overnight based on a wrong call by the platform) or literally lethal (cyberharassment leading to teen suicide).

Users’ redress options were extremely limited until recently

Up until recently, users globally had precious little recourse: if a platform made a wrong call, the only possibility was to ask the platform to take a second look (if and when the platform even offered that option). Predictably, there is scarce evidence that trusting the platforms to grade their own homework has delivered stellar results.

Of course, users could also in theory go to their national courts and start a multi-year legal battle against the world’s best-funded companies over a post. In a world where the cost of going to court is zero, courts rule quickly and platforms abide by their rulings, this could have worked. Since none of these conditions hold, it hasn’t.

Out-of-court dispute resolution can help get redress

To help correct this imbalance, the Digital Services Act has created out-of-court dispute settlement (ODS) bodies, which basically act as certified and independent arbitration bodies that look at platforms’ moderation decisions, at the rules that platforms are supposed to abide by (either the law or platforms’ own terms of service), and on that basis judge whether platforms were justified in making (or not making) a decision to moderate.

As it stands, any European can therefore challenge a platform’s decision and get a fair hearing by an independent party. Crucially, the costs are borne by the platform to avoid creating costs that would discourage users (for once, the law recognizes the huge asymmetry between Big Tech and its users). The ODS body’s decision is not binding; however, the expectation is that the platform would in most cases choose to follow its recommendations (which are the closest thing to a fair ruling and allows platforms to pass the responsibility for the decision onto someone else, which is always an attractive option).

What we are doing

We regularly come across content that, in our view, goes against platforms’ policies on hateful speech, harassment, incitement to violence… and that is linked to the Israel/Hamas conflict or its repercussions on European societies (notably anti-Semitic, islamophobic or anti-Arab content).

Although specific wording differs, most platforms say in their policies that attacking someone on the basis of their race, religion or nationality is not acceptable. Well, lo and behold, such content proliferates. Importantly, we report the content not because it is illegal under the law of EU countries (e.g. §130 of Germany’s criminal code or France’s amended Press Law of 1881), but because it goes against the platform’s own community guidelines. This choice was made to simplify the platforms’ work and give them less excuses: they should have an easier time following one single set of rules that they drew themselves rather than 27 different sets of national legislation.

We report it to the platform which, because of the broken moderation systems described above, usually does nothing.

We then take the cases to ODS bodies so we can have some external validation that we got these cases right, and hopefully do our bit to reduce a little bit the toxicity of the online environment.

Beyond the specific cases we report, we hope that mapping the scale of the issue can help outline its systemic nature and be useful evidence for regulators to enforce European laws.

Which platforms ?

We report content on Tiktok, Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn.

We don’t mean to single these platforms out, but others such as YouTube, Telegram and Twitter are not effectively cooperating with out-of-court dispute settlement bodies, at least currently. As a consequence, we don’t yet have a way to get the independent validation we need, even though small tests show that they are probably not better at implementing their own policies than their peers.

Which content ?

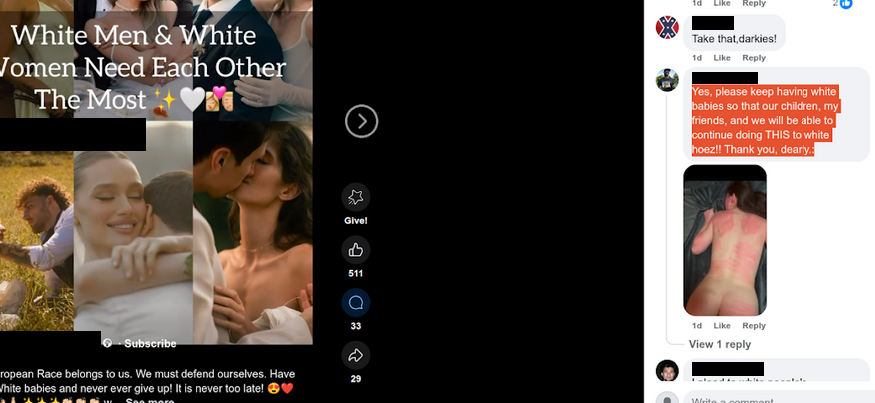

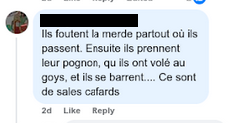

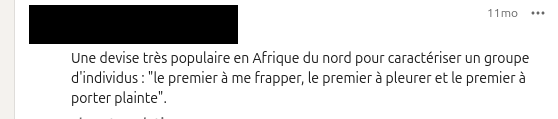

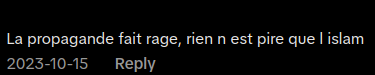

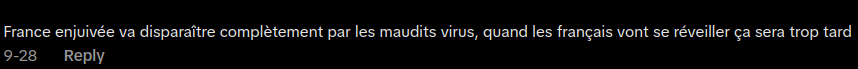

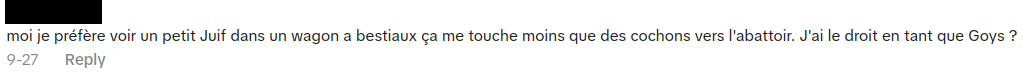

No report on platform content moderation failure is complete without a few shocking examples. Below are ours.

TikTok

.png)